Cover photo by Georg Jacobs.

Find the Little Duskhawker in the FBIS database (Freshwater Biodiversity Information System) here.

Family Aeshnidae

Identification

Richardsbay, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Diana Russell

Large size

Length reaches 68mm; Wingspan attains 87mm.

The Littleduskhawker is a drab brownish dragonfly with smoky, yellowish wings that become darker with age. The sexes are similar but males are a little more colourful with a greenish-brown thorax and a slightly more extensive, blue saddle. Despite its large size Gynacantha manderica is the smallest Duskhawker species in South Africa.

The Little Duskhawker most closely resembles the Eastern Duskhawker (Gynacantha usambarica) but the latter species is green rather than light brown and has 21 to 27 Ax veins in the forewing. Gynacantha manderica has 13-19 Ax veins in the forewing. The two species also have differently shaped black markings on the forehead. The Little Duskhawker may also be mistaken for the Brown Duskhawker (Gynacantha villosa) but that species is far larger and has 22-28 Ax veins in the forewing and a four-celled anal triangle.

Click here for more details on identification of the Little Duskhawker.

Habitat

The Little Duskhawker frequents pools, rivers, streams, and lakes surrounded by dense woodland and riverine forests. It is also often found away from water, hunting in forest clearings. In South Africa the Little Duskhawker generally prefers slightly drier forest and woodland than other duskhawkers.

Photo by Ryan Tippett

Behaviour

The Little Duskhawker is crepuscular, spending the day hidden low down in the shade of dense vegetation. Emerges to hunt at dawn and dusk, and also on warm overcast days. It hunts in clearings or between tree canopies and along wooded pathways. It is often gregarious when foraging and frequently joins mixed species hunting swarms at dusk. The Little Duskhawker has a smooth, rapid flight and it hangs vertically from a perch when at rest. They are sometimes attracted to lights during the twilight hours.

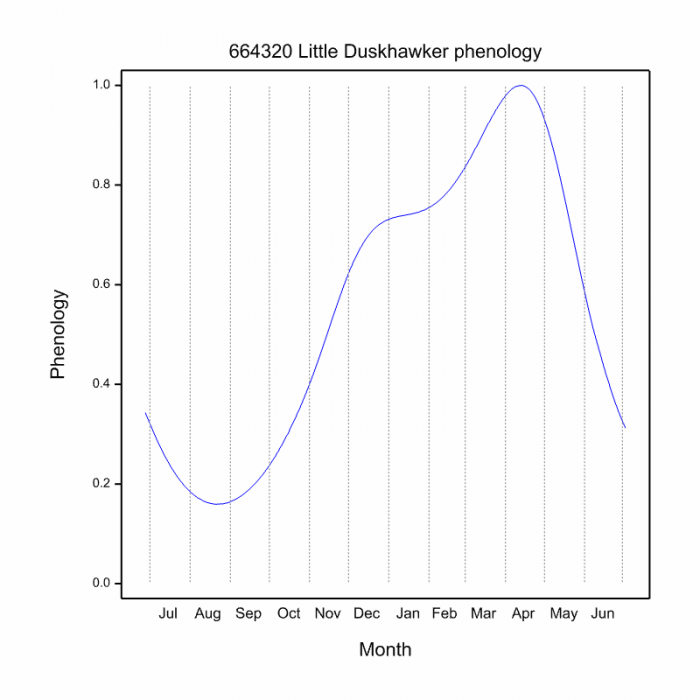

This species is on the wing from September to April (see Phenology below).

Hluhluwe district, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Ryan Tippett

Status and Conservation

The Little Duskhawker is uncommon and localised in South Africa. Listed as of Least Concern in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. This species is sensitive to habitat change and is mostly found in undisturbed, natural habitats.

Hluhluwe district, KwaZulu-Natal

Photo by Ryan Tippett

Distribution

Gynacantha manderica is confined to Sub-Saharan Africa where it is fairly widespread from West Africa, across to East Africa and down to Southern Africa.

In South Africa it is found in the North and East where it is thinly distributed.

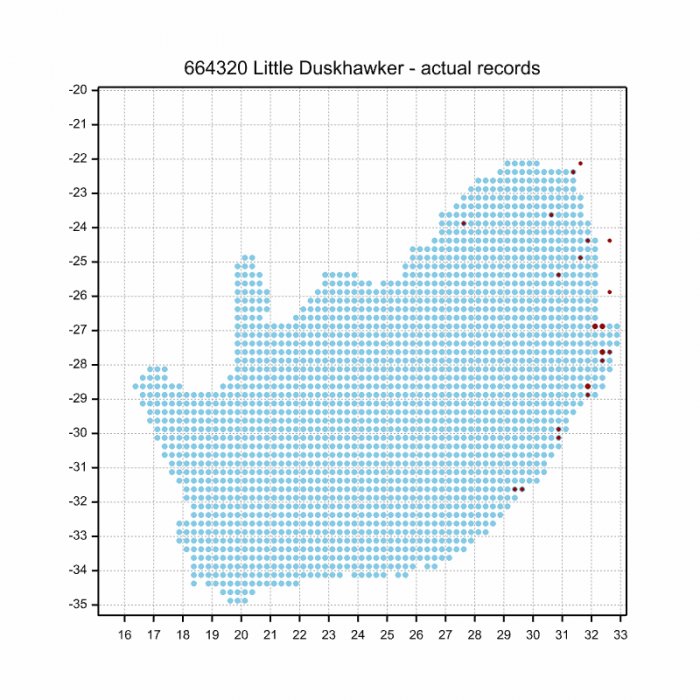

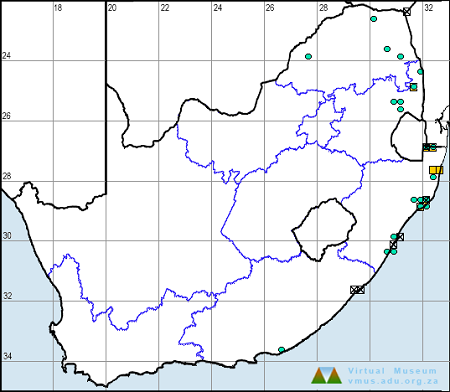

Below is a map showing the distribution of records for Little Duskhawker in the OdonataMAP database as at February 2020.

Below is a map showing the distribution of records for Little Duskhawker in the OdonataMAP database as at December 2024.

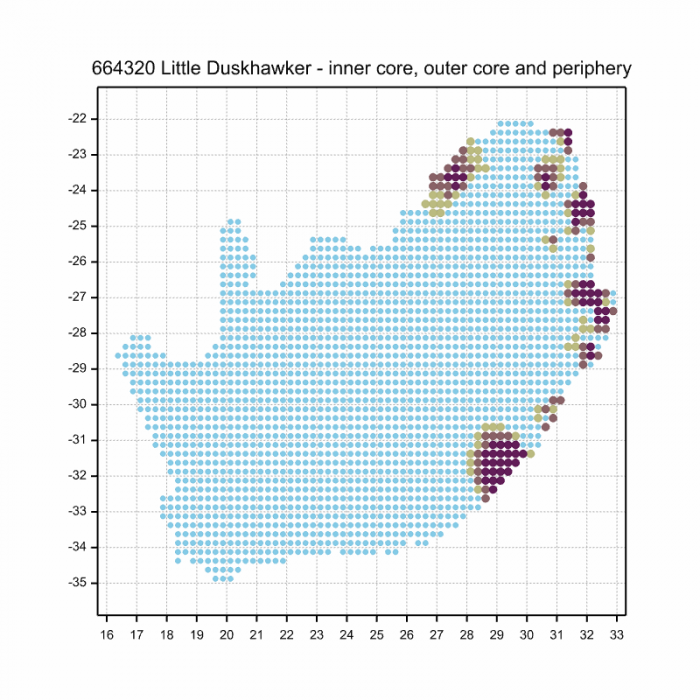

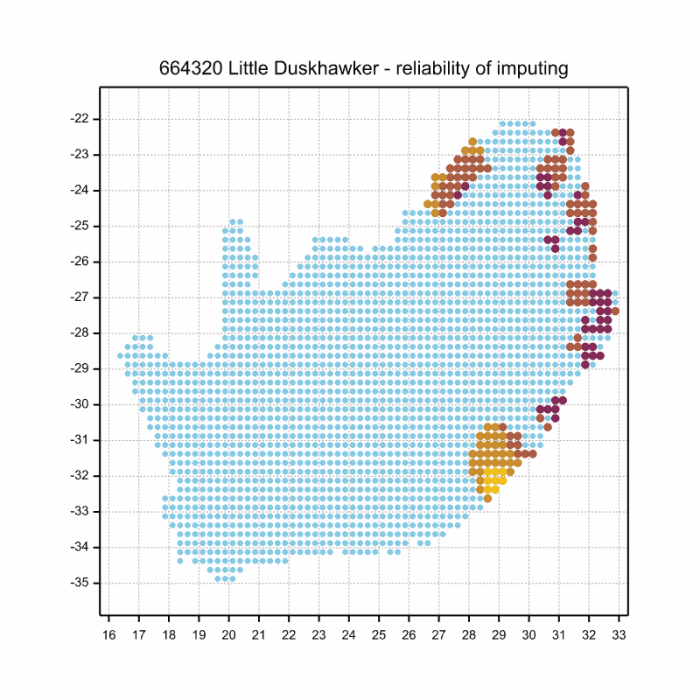

The next map below is an imputed map, produced by an interpolation algorithm, which attempts to generate a full distribution map from the partial information in the map above. This map will be improved by the submission of records to the OdonataMAP section of the Virtual Museum.

Ultimately, we will produce a series of maps for all the odonata species in the region. The current algorithm is a new algorithm. The objective is mainly to produce “smoothed” maps that could go into a field guide for odonata. This basic version of the algorithm (as mapped above) does not make use of “explanatory variables” (e.g. altitude, terrain roughness, presence of freshwater — we will be producing maps that take these variables into account soon). Currently, it only makes use of the OdonataMAP records for the species being mapped, as well as all the other records of all other species. The basic maps are “optimistic” and will generally show ranges to be larger than what they probably are.

These maps use the data in the OdonataMAP section of the Virtual Museum, and also the database assembled by the previous JRS funded project, which was led by Professor Michael Samways and Dr KD Dijkstra.

Phenology

Further Resources

The use of photographs by Dianna Russell and Georg Jacobs is acknowledged.

Little Duskhawker Gynacantha manderica Grünberg, 1902

Other common names: Kleinskemerventer (Afrikaans)

Recommended citation format: Loftie-Eaton M; Navarro R; Tippett RM; Underhill L. 2025. Little Duskhawker Gynacantha manderica. Biodiversity and Development Institute. Available online at https://thebdi.org/2020/05/25/little-duskhawker-gynacantha-manderica/

References: Tarboton, M; Tarboton, W. (2019). A Guide to the Dragonflies & Damselflies of South Africa. Struik Nature.

Samways, MJ. (2008). Dragonflies and Damselflies of South Africa. Pensoft

Samways, MJ. (2016). Manual of Freshwater Assessment for South Africa: Dragonfly Biotic Index. Suricata 2. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria

Martens, A; Suhling, F. (2007). Dragonflies and Damselflies of Namibia. Gamsberg Macmillan.